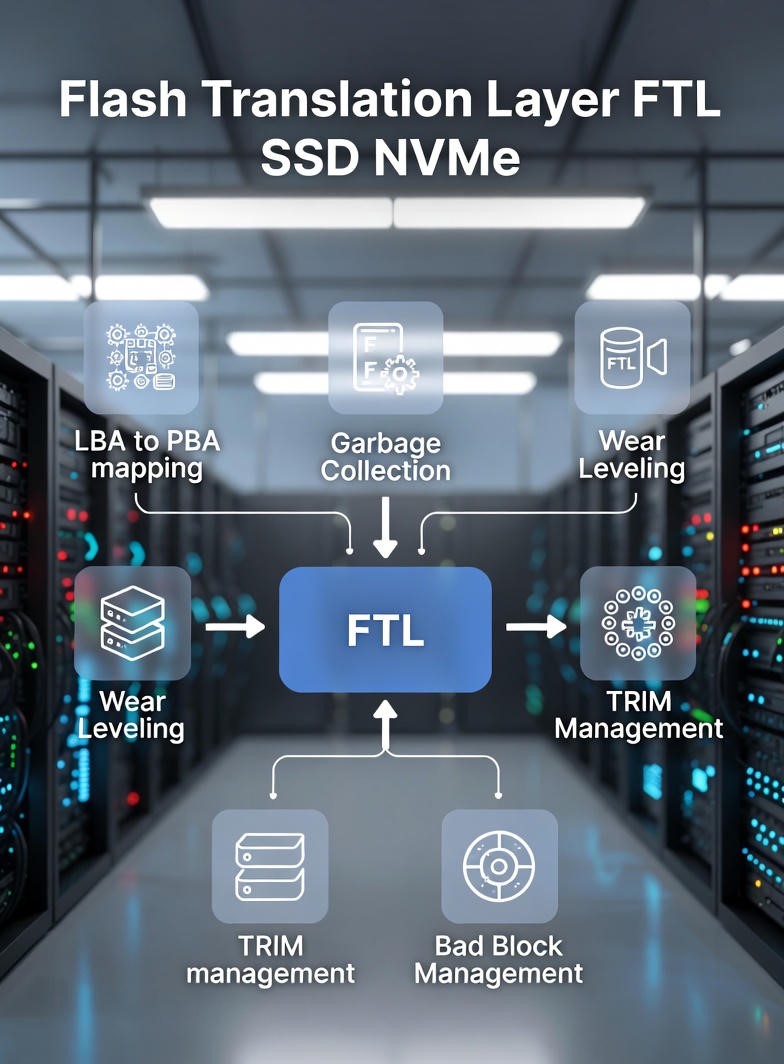

The Flash Translation Layer (FTL) is the firmware that lives inside the SSD/NVMe controller. It acts as the translator between the operating system (which thinks it’s talking to a normal hard drive) and the NAND flash memory, which operates under completely different rules.

Why the FTL exists

NAND flash memory can’t do the simple things the operating system takes for granted:

• You can’t overwrite data in place — you first have to erase an entire block (4–16 MB) even if you only want to change 4 KB.

• Memory cells wear out — TLC/QLC cells only endure 500–3,000 write cycles.

• Blocks are huge compared to the 512-byte or 4 KB sectors the OS uses.

• Bad cells appear over time.

• Without proper management, performance drops dramatically.

The FTL handles all of this in the background so Windows, Linux, or macOS never notice.

What the FTL actually does (2024–2025 version)

1. LBA → PBA Mapping

Translates the logical block address the OS sees (e.g., “file X is in sector 1,234,567”) to the real physical location inside the NAND chips (Chip 2 → Die 4 → Block 8923 → Page 127).

This mapping table is kept in the controller’s DRAM and periodically saved to NAND.

2. Garbage Collection

When blocks become partially empty, it copies the still-valid pages to a new location and erases the old block so it can be reused.

3. Wear Leveling

Moves “cold” data (files that rarely change) to heavily used blocks and vice versa, ensuring the entire SSD wears evenly.

4. TRIM Management

When you delete a file, the OS sends a TRIM command. The FTL simply marks those pages as invalid but doesn’t physically erase them until garbage collection runs.

5. Bad Block Management

Detects failing pages/blocks and removes them from the map. SSDs reserve 7–28 % extra capacity from the factory (over-provisioning) precisely for this.

6. Hot/Cold Data Separation & SLC Cache

Temporary files go to fast SLC mode; important documents go to denser TLC/QLC areas.

How all this affects data recovery

When everything works → the FTL is your friend.

When something goes wrong → it becomes your worst enemy.

• Normal file deletion

Data remains physically on the NAND even though the OS no longer sees it. As long as garbage collection hasn’t run, recovery is nearly 100 % with standard tools (R-Studio, DMDE, etc.).

• Quick format

Windows sends TRIM to the entire drive. The FTL marks ALL pages as invalid. To normal software the drive looks empty, but the data is still there… until garbage collection physically erases it.

• Sudden power loss

The LBA→PBA map stored in DRAM is lost. On reboot the SSD doesn’t know where anything is — it may enter safe mode, show 0 GB, or appear as RAW.

• Controller/firmware failure or corruption

The map is lost or inaccessible. Even if the NAND chips are perfect, the drive won’t boot and may show as uninitialized or not detected in BIOS at all.

• Heavy use after deletion/format

The more you write afterward, the more garbage collection runs and the more data gets permanently erased.

Real-world cases and current success rates (2025)

• Just deleted files and powered off immediately → 95–99 % logical recovery.

• Quick format + very little use afterward → still 80–95 % with normal software.

• Drive was nearly full and heavily used after the incident → 20–60 % (much data already overwritten by GC).

• Power loss + lost map → logical recovery almost impossible (0–30 %). Lab required.

• Dead controller or corrupted firmware → 0 % logical; needs physical chip-off (65–85 % success in good labs).

Golden rules to avoid losing your data on an SSD/NVMe

1. As soon as something feels wrong → disconnect the drive immediately (physically if possible). Every second it stays powered can trigger garbage collection.

2. Never run chkdsk, never accept formatting, never initialize in Disk Management.

3. Always create a bit-for-bit clone first (ddrescue on Linux or HDDSuperClone).

4. If possible, temporarily disable TRIM before connecting the damaged drive:

fsutil behavior set DisableDeleteNotify 1 (Windows).

5. If the drive shows 0 GB capacity or isn’t detected in BIOS → go straight to a lab with PC-3000 Flash or equivalent. Time is against you.

In short: the FTL makes your SSD fast, reliable, and easy to use… but it’s also the component that can irreversibly erase your data even though it’s still physically present on the chips. The faster you act and the less the drive is used after the problem, the higher your chances of recovery.